How to keep a lab journal

Keeping a lab journal is, above all, an act of discipline. You need consistency and a set of rules on which you have agreed yourself. Getting started is easy, but making it grow is hard.

A lab journal is a bet for the long term, which means it must be written in a clear and consistent way. There are many reasons to answer why keeping a lab journal, and the only way of being successful in all of them is to know how to approach it.

For me, a lab journal is the best tool to slow down and think about what is being done. Forcing me to write down gives me enough mental time to think before I do.

And, if I should pick a single reason why to keep a lab journal it would be that: to slow down the pace at which we do things in order to reflect on them.

Getting started

The first thing to do is to establish some ground rules on what a lab journal must be and must have. Unless you work in an automated setting, there is no way to beat a paper log book, so the rest of this guide is focused on the assumption you are writing on paper.

Type of log book

(Read more on Requirements of a Lab Journal)

The first thing you need is a paper note book that must conform to some basic standards to work as a lab journal. The most important:

- Pages can't be ripped out. This rules out binders, notebooks with rings, etc. Pages must be bound to the journal.

- Numbered pages. This can be done by hand as you progress with the use of the journal.

- Hard cover. Although not a strict requirement, lab journals must be resilient to their context, for instance spilling a mild solvent like acetone on them. Grabbing them with dirty gloves, etc.

- Page design. Some people like ruled books, some people like dots, others like squared. I used what I get at hand. It is a matter of personal taste what makes you work smoother.

There are some custom-made lab journals that are over the top expensive with very little added value.

First things to write down

As soon as you get a new lab journal, you must make it yours. A good idea is to put your name on the cover (with a sticker, for example) so that people can immediately know who is the owner. It is also a good idea to write the starting date of the journal.

On the first page of the journal, write down your name, contact details, including relevant information such as in which lab you work. This not only helps return the lab journal to the owner, but it also helps speed up the process of seeking help in case something happens to you while working (for example, if you are working in a shared facility.)

Index for the journal. The first two pages of the journal can be left empty to create an index.

An index is useful to quickly find interesting things back, like the protocol for sample preparation, settings for a measurement, etc. It is definitely useful if you work on many different things and your brain is switching contexts often.

Using the Lab Journal

The purpose of a lab journal is to document what you do, what you observe, and what you think in the moment.

Some day it may be useful in case of a patent dispute, but most likely it is going to be useful for yourself to understand your train of thought, to reproduce results, and to build on what you have done without the need to re-run experiments.

The most important thing to keep in your head is that you can't trust your own mind. As sad as it sounds, never believe you will remember something in a month from now, not even tomorrow.

The information must be complete. A good lab journal contains information on what steps you followed to prepare a sample, write down any deviations such as using an old stock solution that had a strange color. It should also document how experiments are performed, settings, and observations done in the moment, such as: there was a strange vibration in the building at the moment.

To make it useful, there are a couple of patterns that are worth observing.

Start with a date

A lab journal is chronologically ordered. Every time you sit down at the bench, you must start on a blank page writing down the date at the top.

Of course, be sure the page you are using is numbered, if not, keep adding numbers in increasing order so that each page you use is numbered before you use it.

Having clear dates are fundamental to finding data back (as discussed later). The lab journal is the best piece of metadata there'll ever be. Digital metadata is useful, but the context in which experiments are performed is even more relevant.

Sure, dates may also help in legal claims regarding discoveries and intellectual property. There are some anecdotes regarding the invention of the telephone, and CRISPR-Cas9 that may be cautionary tales of why it is important to keep an ordered journal.

Whether each day should start on a new page is a matter of taste. I like writing in blocks so all the relevant information is on the same page. If I see a block won't fit in the remaining of the page when starting a new day, I simply start on a new one.

In a strict sense, a lab journal should not have empty spaces to prevent altering it retroactively. Once your day is done, you can cross the remaining of the page to indicate nothing else is done.

Write what you do

Each experimentalist will have different flows during their days, but the patterns are always repeated.

For example, people doing experiments that require strict temperature stability, may write down the room temperature as soon as they start their days. It may help you discover that the room in summer is colder than in winter, contrary to common assumptions.

If you have a protocol for sample preparations, for example, you should write it down once. Since pages are numbered, every time you use that protocol you can reference back to it easily.

If you develop a new version of a protocol and want to avoid using the old one by mistake, you can use a post-it note to mark it down. By no means alter the past. Don't cross over or change an older protocol. Experiments done based on it will lose their sense. Spend some time re-writing.

When you are about to perform a measurement, make sure you have all the relevant parameters written down. The key here is relevant. If you do an experiment, you are probably trying to test something, you found out what are the optimum settings for the instruments you use, etc. That's very useful information that must be logged down.

Digital metadata is helpful but not always available, and you have no control over what is being stored. If you write it down, you fully own it.

There must be a correlation between what you write down and the data being saved, which I discuss later.

Write what you observe

Observations while doing an experiment are incredibly important.

For example if you see something going wrong with the measurement and you stop it. Months later, when you are looking at your data, it will incredibly frustrating not understanding why some things are incomplete, or spending time looking at something you already knew it was wrong.

Write what you think

Write down as much as you can about what you think while doing experiments. For example, what are you trying to achieve? Sometimes you know it very well, sometimes you are doing things someone asked you to.

If you see something interesting but have no time to pursue at this moment, write it down. Once it's on paper, you know it can be found back.

Sometimes you may think "tomorrow I would like to do this..." but tomorrow got swamped with meetings, and the day after the equipment is busy, and suddenly a colleague asked for help, and the weekend comes, and a week later you already lost the train of thought.

Saving data

The final aspect of lab journals is that they must correlate with what is done in the real world, not just on paper.

In almost every single lab experiments are ran through a PC that saves data. It is paramount that there is a one-to-one relationship between the data and the information stored in the journal.

Data must be stored in a time-based structure. If data has a clear time stamp, it is easy to go back to the lab journal and find out what was happening on that moment.

I normally create folders with the following pattern: YYYY-MM-DD, like 2023-03-08. Then I can quickly go back to my journal and understand what was going on or the other way around.

The other important thing is to have clear file names (or folder names) without creating an overflow of information.

For example, I try to use file names that reflect the most important aspect of what is being measured. If I am working with particles of different materials, I use the material as the file name. Then, I store each data set with an increasing number. I get something like:

2023-03-08/

Polystyrene_1.dat

Polystyrene_2.dat

Silica_1.dat

Silica_2.dat

And in my lab journal, under the day 2023-03-08 I would write down something like:

Polystyrene nanoparticle sample prepared as in page 32.

Silica sample prepared as p. 25.

Polystyrene_1: 90nm nanoparticles in water. Exposure

time 5ms.

Data looks good.

Polystyrene_2: Idem 1, but exposure time 10ms. Data

looks good.

Silica_1: 100nm nanoparticles, 5ms exposure. Particles

were too dim!

Silica_2: idem, 50ms exposure. Data looks OK, but I

think it can be done better with a different wavelength.

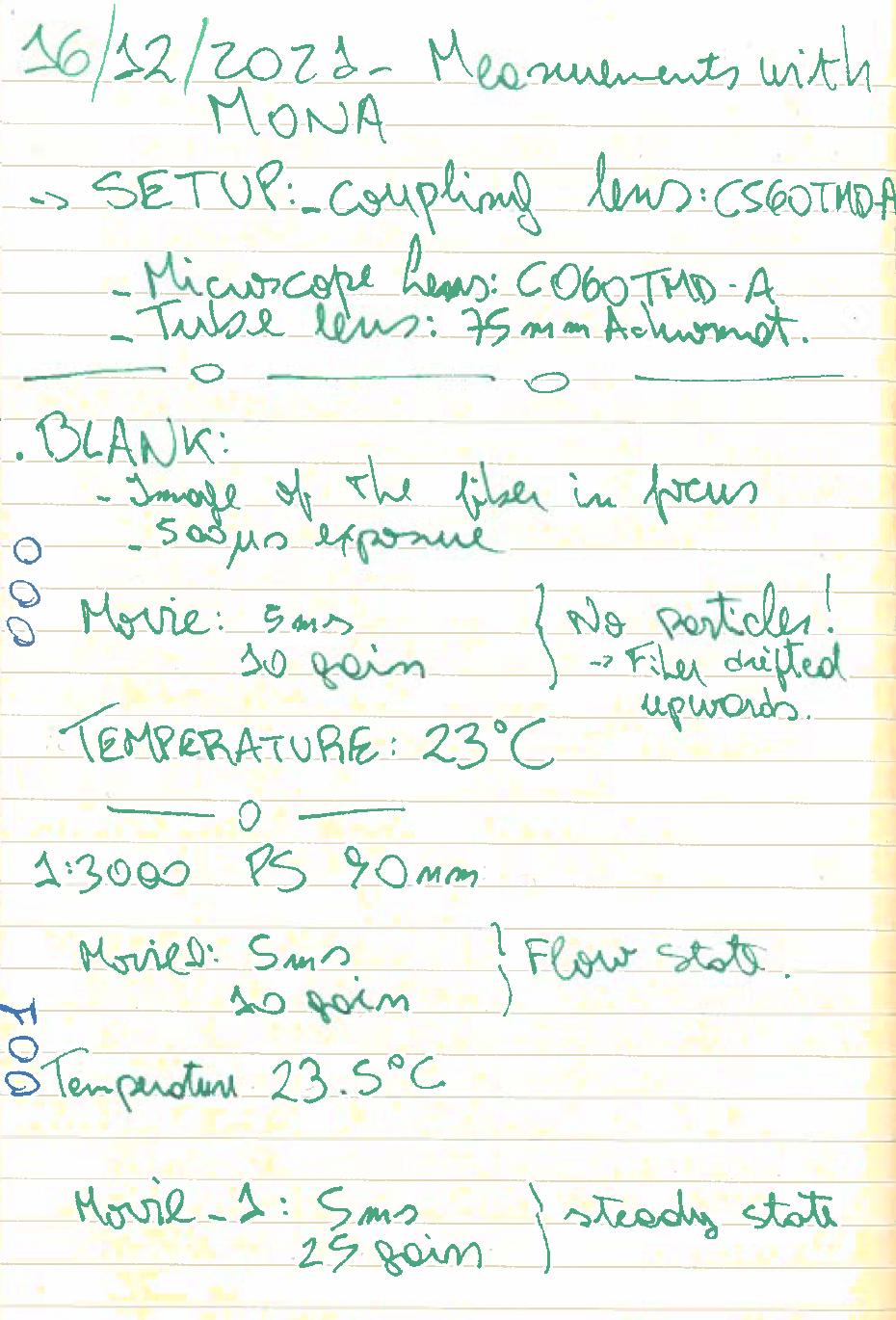

This is a real example of how a page of my lab journal looks like:

On shared equipment

On equipment and computers that are shared between people, it is of utmost importance to write down who acquired each dataset, or it'll be a nightmare to find out which lab journal to check.

A healthy habit is to create folders for different users, and inside the folder to keep the date-based structure.

Of course, the best approach on shared equipment is to agree on a standard flow everyone will follow, so it becomes clear who is the owner of each file, and what can be done with it.

Backlinks

These are the other notes that link to this one.